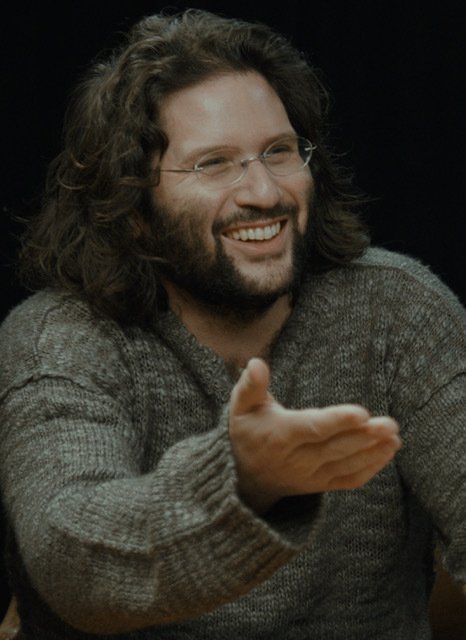

Michael Fertik interviewed by Sandra Fluck

Michael Fertik

Michael Fertik is a published fiction author, poet, produced film writer, and playwright whose writing has won fiction, poetry, and film prizes and includes a New York Times Bestseller. His novella Allotrope was published in The Write Launch and a review of his book Hip Set is available on bookscover2cover. Michael is a graduate of Harvard Law School and lives in Palo Alto, California.

Michael Fertik interviewed by Sandra Fluck

Your novel Hip Set fits the genre of a detective mystery, but the novel’s literary motifs go beyond this generic description. How would you describe Hip Set to interested readers?

Hip Set is noir, which is my favorite form of mystery fiction. In my opinion, noir is one of the three genuinely, originally American art forms – the others are jazz and its progeny and the Western movie. (You might have your own list.) The essential elements of noir have remained the same for 75 years. An incorruptible detective, who is often also emotionally and physically apart, journeys through the beautiful and ugly parts of a city in relentless pursuit of the killer. In a well-wrought noir, even more so than in other forms of detective story, the particularity of the city itself is indispensable, and that particularity must include unique forms of socioeconomic upheaval, political intrigue, and enough social mobility to make the striving of its citizens – and the murder that animates the story – worth the trouble. The noir of Hip Set unfolds as a police procedural. But that narrative form takes an unexpected and important turn, true to the spirit of noir, when we learn that the story, which takes place in present-day Tel Aviv, actually began in biblical time.

For novelists, there is always the “thinking” stage prior to the first act of writing. What did your “thinking” stage encompass?

I agree, the thinking stage is immensely important. Often, when I am beginning to write something new, I will compel myself to sit still, sometimes for hours, until a good enough idea occurs to me, and then I will not let myself leave that place until I have captured a flood of notes that follow. Then there comes an extended period of research, over a period of months or longer, to learn how to talk about the setting or character so thoroughly that it starts to hold up to the scrutiny of natives or other subject matter experts. This is both grueling and full of fun. Well, in the case of Hip Set, I did all of this except the first part. I am reminded of a story told by George Gershwin about his having composed Rhapsody in Blue, almost one hundred years ago. He said that, over the course of a train ride from New York to Boston, the structure of the entire work appeared to him virtually at once. A few years ago, I was on the beach in Tel Aviv, on what they call the Tayelet, the boardwalk, which runs the length of the city. It was 430 or 5 in the morning, before the sun had come up, when the notion of the morning is just starting to give itself to the sky. I was bleary eyed from the brutal jet lag that never fails to hit you when you travel from the West Coast to Israel. And I said to myself, just like that, I love noir, and I am going to set one in Tel Aviv. I had my notebook with me, as I usually do. I opened it, took a sip of Americano, and wrote the first lines. I had the basic outline within an hour. This was lucky.

Oscar Orleans, the main character in Hip Set, has a genesis story. When did you begin to “see” Oscar?

Setting a novel in Israel is fraught with risk. There are so many stories a typical reader would understandably “expect” to find set in Israel, and I did not want to write any of them in Hip Set. In this particular novel, I wanted to tell a story that, while, inextricably tied to its place, did not unfold, for example, in the context of the Israeli-Arab conflict. I also wanted the book to have the “right” to comment on Israel and Tel Aviv as modern-day phenomena. For that reason, I needed to tell the story from the point of view of an outsider. I did not want the main protagonist to be a sabra (native born Israeli) or Palestinian local, who might each have had terrific insights but for whom wry detachment might have been harder to make plausible. I did not even want to tell the story through the eyes of an American or French transplant, as I could have foreseen spending needless pages leaning against figurative or tropological expectations. Far better to get an actual outsider who comes from a different place, a different culture, a different idiom but who has lived there long enough to have become a sharp-eyed expert in the local life. It is a useful device, deployed for centuries by writers as wide-ranging as Herman Melville in Ishmael and Agatha Christie in Poirot. Hip Set unfolds in the milieu of the Sudanese refugee population of Tel Aviv. It is a fascinating fact of Israeli life, that a group of non-Jewish, non-Arab immigrants have arrived seeking religious and political freedom and economic opportunity. I conceived Oscar Orleans as a nearly unique figure: an African who had arrived, alone, in Israel many years before the Sudanese refugees, but who had been named upon their arrival, in the absence of any other obvious candidate, as a kind of semi-official liaison to the Sudanese refugees, even though he was from Congo, over 2,000 kilometers away from Sudan. Oscar himself is a combination of people I have met and researched, but the primary inspiration was a real person about whom I read in a magazine, who had undertaken many life-risking steps to get to Israel and whose main life goal, as far as I could tell, was eventually to become Israeli. Also: in my mind, Oscar looks and moves something like the actor Lance Reddick. I have never told anyone that before.

When Oscar flees Congo, he travels north and ends his journey in Israel, the setting for Hip Set. Why Israel?

In the past quarter century, Israel has undergone a stunning economic transformation that is well known to those who live in or visit the region frequently but is otherwise overlooked in conventional discussions of the Middle East. Until quite recently, Israel was basically a poor, agricultural country dominated by a European socialist political culture. A revolution has unfolded since the tech boom started in the late 1990s. Israel is now a (mini) economic powerhouse. Tremendous wealth has appeared. Gleaming skyscrapers have been built. International boutique hotels catering to glitterati have cropped up in different parts of the country. It has all happened very fast. Think of the California Gold Rush of 1849. For the first time ever, Israel has become a destination that is desirable not only to religious populations and a handful of ethnic groups. Israel is now one of the more attractive places within thousands of miles for people who want to make a better life. This new chapter has brought with it many unexpected changes, and it is one of the main animating underlying forces of Hip Set. Oscar himself arrived in Israel toward the beginning of this shift, but it is especially important for what is happening as the novel unfolds.

When did you realize the myth of the Queen of Sheba would play a significant role in Hip Set? How would you characterize the tone of this chapter relative to the tone of other chapters? How many revisions did you write before you were satisfied with it?

The Queen of Sheba chapter gets more attention and questions than any other. It is told in an entirely different idiom from the rest of the book. The chapter most closely resembles fable or parable or what the Jewish tradition would probably call aggadic midrash. This chapter also explains, finally, the meaning of the book’s title Hip Set, about which the reader is given some red herrings beforehand. The Queen of Sheba chapter is told as a story within a story, nested in the same way biblical and traditional narratives often are, and it represents a tonal, expressive, and temporal turn in the book that reveals the design of Hip Set to be not only a detective inquiry into a murder but a continuation of a millennia-old mystery. I knew I had to tell this story in the book. But I did not know, till very late, that it had to be imparted in this way. There had to be a break – a believable, inviting, sonorous break – with the voice of a procedural noir and into the language of bible and endless time, in order to give over this part of the tale.

You are the author of The Reputation Economy, a bestseller on The New York Times list. Four years later you published Hip Set. What did you learn from writing the earlier book that you applied to Hip Set?

Nonfiction business-or thought-type books and fiction are so very different. But I have learned that the publishing world in both parts of the house is none too easy or forgiving. It barely works, actually. One observation probably covers most of the territory. Nearly every agent, editor, or publisher, is chiefly in the business of guessing what nameless, faceless “other people” would do or think. (This is often expressed, over-simply, as some form of “we would totally do this, but the other idiots over there wouldn’t get it, so our hands are tied.”) Nearly no one makes up his or her own mind. Nearly no one wants to do something because it feels or looks right. Never mind the “economically-based” decisions: I have still not once met someone in publishing who can read, let alone use, a spreadsheet, but these very nice individuals have picked up the language of business school when they talk about “data-driven” choices for publishing. It’s bananas. And once you’re published, you’re mostly paddling a solo canoe. The publishing houses offer, without exaggeration, something like a single tweet of support for your book. Reviewers are basically gone. The business is in a state of collapse. It’s bleak. You’re basically on your own as an author, though you do get to encounter some terrific souls along the way (including Sandra Fluck—no irony!). In some sense, there is a clear connection between writing and my day job as a technology entrepreneur and investor: all day long, more than anything else, I look for people who make up their own minds. It’s a very low hit rate, but it is hugely rewarding when you find someone who fits the bill.

What kind of a reader were you as a child and/or teenager? What books did you read?

Thank you for asking! I do think this is important. I read all the time. I was the kid with the book in hand everywhere he went. By contrast, I wasn’t an athlete until high school, basically. I read fiction and non-fiction, mostly history, and I read widely. But I did not have an interest in fantasy or science fiction, even literary examples, except maybe for some Primo Levi. I still don’t. This past summer, I tried Philip K. Dick, just to give it another go. Though I liked and admired Man in the High Castle, I couldn’t even finish The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch. I consider constituent elements of sci-fi and fantasy to be limitations, even as others must find them to be strengths. About fifty-percent of the entire work is exposition. It has to be, because you’re in a new setting, and that’s part of the charm. You have to explain why it’s so hot outside or why there are one and a half-moons or how the dragons or other humanoid creatures got to be that way. The most disappointing thing is how unradical it is. How do we know that? Because the value systems presented in those books are still the same. The book is told to us by one of us, so the basic value systems that are presented as right or wrong (“treat people in such a way”), and the basic narrative ideas (“he gets or returns to the girl after realizing his failings”) are all seen through our eyes. Which means so much of the exposition is just window dressing. Romeo and Juliet on Mars. I think the imagination required for alternate history or science fiction is worthy, but I also think it is often mistaken for creativity. No doubt many disagree with me. For many years, starting sometime after college or so, I read much less than I had as a kid. Life just got so full with other responsibilities that I couldn’t really read serious stuff even when I made the time. In the past couple of years, due to some changes in my life, thank G-d, I was able to start reading a lot again, and the biggest thrill is that that kid had been, all this time, waiting for me to find him. I kinda couldn’t believe it. Nowadays, in any given week, I probably read two to four books.

What books are you reading now? What books do you recommend to writers?

I have been reading a lot of the Library of America volumes. I have a particular fondness for American literature, and I am distinctly proud of it. (“Let ‘em all go to hell, except Cave 76…!”) Lately I have been reading 20th century authors like James Baldwin, Elizabeth Spencer, John O’Hara, and John Williams, but I also just finished a volume of Lafcadio Hearn, who died in 1904. Library of America is useful because they do a lot of the work for you, finding both the obvious chestnuts and the hidden gems and putting them in one place; often enough that will include essays or articles or short stories that give hints of whence they came or where they were heading at various times. I have sometimes read one or two of the pieces in a volume before picking it up, but always a lot is new to me, and it’s valuable to have it all in one place. You get to see the good and less good, and you get to see the development, and you understand more of when they were trying something on and when they were nailing it. I haven’t done a heavy dose of this series since college, probably, when I was fairly steeped in it. The editing is too variable, though, and I sometimes wish it were more consistent. And I also wish the print were slightly larger, as it is somewhat preciously small. Anyway, I am on an American kick for some time, and I am enjoying it, so we’ll see how far it takes me. As to what I recommend: of course, I agree with everyone who says that reading makes better writing and that writers are readers. But I find I change my mind over time over whether I think it is important to read mostly in the genres in which you aim to write or in others.

When did you know you were going to be an author? Who were your mentors? Influencers? What advice did they give you?

I think my dad gave me the bug. I believe my dad always wanted to be a writer, and he wrote a lot, and his set pieces and dialogues were very, very strong, but I think he never could quite wrap up a tale with a narrative bow in the way he wanted. My father, grandfather, and great-grandfather all made their living as visual artists. My brother does, too, at least in some measure. And my older son, thank G-d, has some kind of gift in the visual arts. But I think my dad wanted to be a writer, and he urged me along until, at some point, I found it was part of me. Anyway, the visual art part seems to have skipped me. I haven’t had fiction writing teachers.

You are giving a talk to high school students about a writing future. What do you tell them?

First of all, write it for yourself.

Many fans of Hip Set are looking forward to a sequel (or sequels). What do you tell them?

Your lips to G-d’s ears.